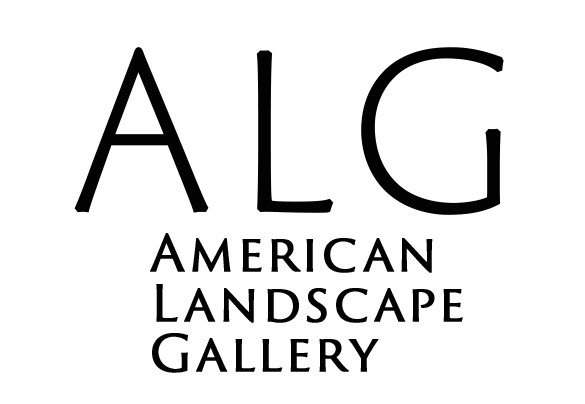

A young boy steadies his brother so he won’t remove the intravenous drip at camp Khao-I-Dang.

The Silent Cries

This collection of images is from various camps that I visited; Sa Kaeo, Khao-I-Dang, Camp 007, Ban Mak Mun and other smaller refugee camps. As I stare at these images, there is little that I can say about these children in their moments of need. The images speak for themselves of their confusion, their pain and their hope. Even after all these years there is sad power in these images which need to be shared if only so we do not forget this human tragedy.

I still can’t get over that in our shared humanity, we allowed these events to happen. Today, the children of Cambodia have no knowledge of this terrible past. Only a small portion of Cambodia’s over 50 population remember those years. Many still suffer emotional damage from that dark past.

Clinging to life in the Khao-I-Dang medical tent.

“Your children are not your children…they are the sons and daughters of life’s longing for itself.

KAHLIL GIBRAN, THE PROPHET.

A mother and son under medical care and safety in Khao-I-Damg.

“There can be no keener revelation of a society’s soul than the way in which it treats its children.”

Nelson Mandela, Former President of South Africa

Dedicated Doctors

Various government and non-government organizations came to the Thailand border in late 1979 to tend to the estimated 500,000 refuges trying to escape Canbodia's famine and fighting. The American Refugee Committee, based in Minneapolis brought in a number of doctors and nurses to work in the new camp, Khao-I-Dang. Dr. Robert Beck, a young Minnesota physician working for World Relief was particularly concerned about the effect of prolonged malnutrition on the young children’s mental development. The American Refugee Committee now works under the name “Alight.”

Dr. Carolyn McKay of St. Paul Ramsey Hospital, a Pediatrician and expert on malnourished children working at Khao-I-Dang. Dr, McKay went on to be Minneapolis Health Commissioner.

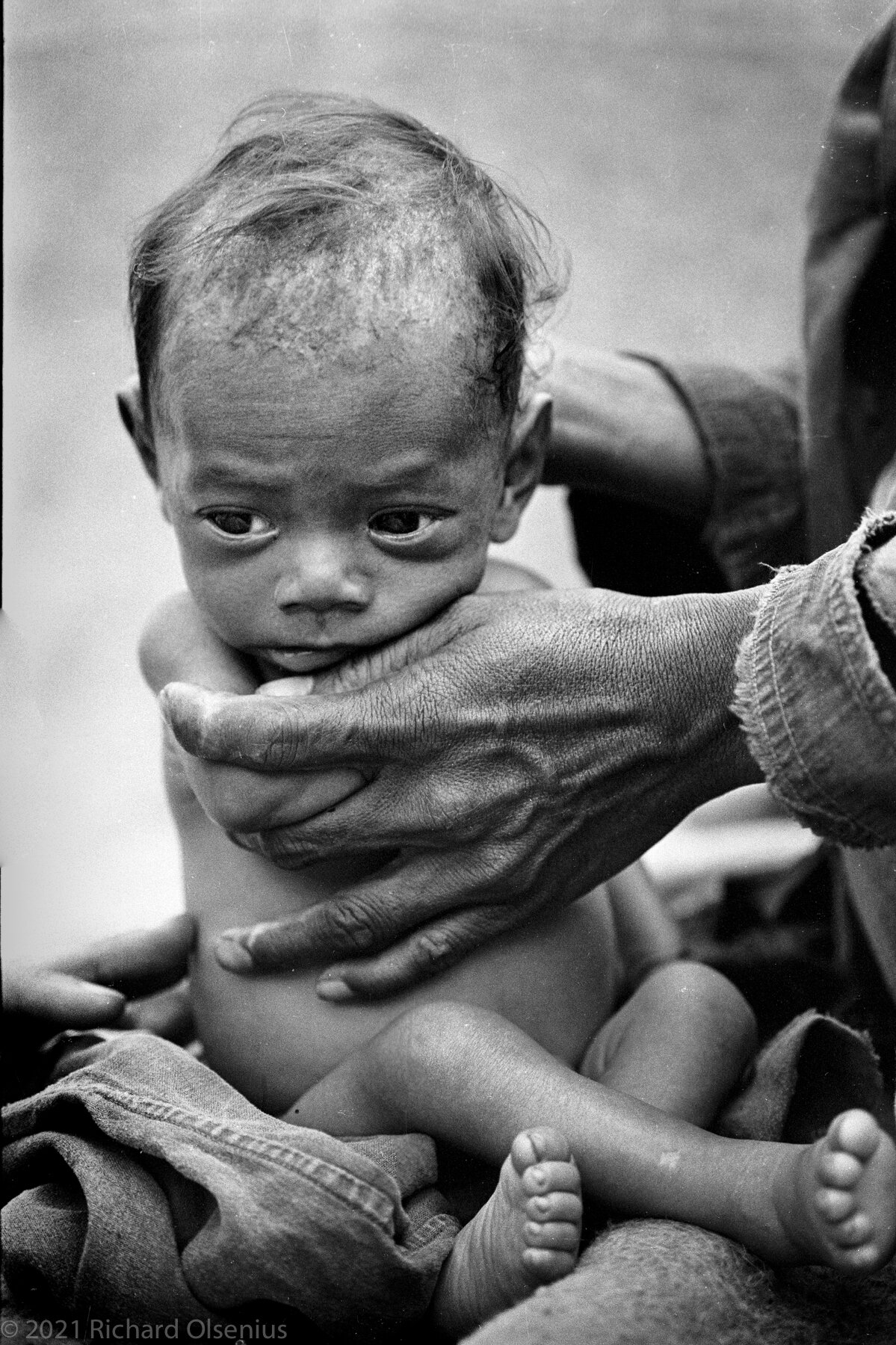

Dr. Steven Miles of Minneapolis said that seeing babies who look like living skeletons and children with weakened bodies is the visible part of this problem, but brain development is a greater concern. Dr. Miles went on to practice medicine and teach medicine and medical ethics at the University of Minnesota.

Pat Walker at this time was a third year student at the Mayo Medical School. working in Khao-I-Dang. Today she is a Doctor of Medicine and is director of HealthPartners Center for International Health and a former medical director of this refugee camp in Thailand.

Pat Walker (rt.) was a third-year medical student at Mayo Medical school with an interest in nutrition and later became a Doctor in Minnesota.

She and Debra Turk, RN (left) were there on behalf of the American Refugee Committee now known as Alright.

A young boy wounded by Vietnamese soldiers

The malnourished children were too week to eat and had to be fed a solution through a feeding tube.

Each day the tent reserved for the dead waits for a team to come and remove them. The young children that found their way here was the most troubling.

Blessed are the Children

A mother steadies her child who is severely malnourished.

A Generation Passes

These images have sat neatly layered in an 11 x 14 Kodak paper box for 42 years. I thought of them often, sitting there on the shelf in Minnesota, and then on a shelf in Maryland and finally in a garage just south of Tucson, Arizona.

Is there a reason to feel guilty about just letting these images from the “killing fields” of Cambodia lie in peace all these years? Not really, I tell myself. They gave a face to a tragedy that most Americans were unaware of and provided newspaper coverage that helped raise millions of dollars to save and treat Cambodian refugees in 1979-80.

But these images are part of an historical continuum. They live as markers in time, of the impacts that war, upheaval and political division can have on innocent populations.

So watching the political division grow in the United States and abroad, where dangerous feelings of “us and them” are gaining strength and becoming violent, I wanted to bring this collection back into the light of day. No matter the country, the legacy of violent, totalitarian regimes is one that destroys reason, justice and humanity. We need to be vigilant.

There are no cries if no one hears.

There are no cries if no one hears. Walking through the medical tents is difficult, there is no other way to say it. With the cots placed one right next to the other, there is no personal space for these mothers and their children. In Western norms, I am trespassing, yet no one seems to mind. Everyone getting treatment seems to be extremely thankful and having a photographer in their midst is the least of their problems. I’ve always felt that tinge of guilt, that I was taking more then I was giving. But it’s the journalists’ job to take back a story. If being overly sensitive makes one turn away from the brutal reality we sometime face, there is no one else to tell the story. It is like the philosophical thought, “If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?”

So the children of Khao-I-Dang need us all, the mothers, the doctors and the journalists. We have to save the children and we have to prevent this from ever happening again.

Cradled on his mother’s lap, a child silently waits for his strength to recover.

There is an eerie silence in the medical tent where scores of children are fed intravenously.

Hope & Endurance

Somreth Bunkytek and his wife Ly Kim Sreng with their children

Hope at Khao-I-Dang

Top photo - Somreth Bunkytek and his wife, Ly Kim Sreng, and their children, Sophal, 8, Phala, 12, and Sovann, 4, sat in a hospital hut in Khao-l-Dang where he was working as an interpreter. They hoped to emigrate to the United States. In 1975 after everyone was forced into the countryside, the Khmer Rouge lead by Pol Pot announced over loudspeakers that doctors, teachers and nurses should step forward.

“They took them away and as we later found out, killed them,” said Somreth. “They wanted to kill all the intellectuals.” Somreth, who speaks French, English and Cambodian, would have fit that bill, too. So for the four years that the Pol Pot Communists ruled, "I acted like I'm stupid — so I could live. I never spoke English or French at all" (Mpls Tribune Picture Magazine 13 Jan 1980)

I do not know what became of the Bunkytek family other that on Feb 11th, 1981 they flew into Chicago’s O’Hara airport to start their new life in DeKalb, Illinois. I discovered that in 1985, Bunkytek received a degree in business data processing with honors from Kishwaukee College in Malta, Illinois.

A young woman at Khao-I-Deng with child waiting for for the food line to form.

I have lost many of the names of families I photographed. I spent nearly a month in the camps and I rarely had an interpreter. I placed myself in and around the few square feet of family spaces. There were only a few seconds where body language and eye-contact would either open or close that brief moment allowing me to photograph in their personal space. My heart is still touched by their openness 42 years later.

There is no explanation for the enduring resilience of the human spirit, especially for those who journeyed through the hell of Pol Pot’s killing fields. Cambodians exhibited a will to live and prevail, to start a new life amid the devastation of war. Many emigrated to France and the United States with little more than the few possessions they could carry. Many returned to the wreckage of their native country to rebuild it and their lives. There are a million stories that we will never hear from those who did not survive this tragic time. That is why Shadows in the Sun was created, to ensure that we will not forget one of the worst chapters of genocide in the world.

Richard Olsenius

Children still found a way to be children in Khao-I-Dang.